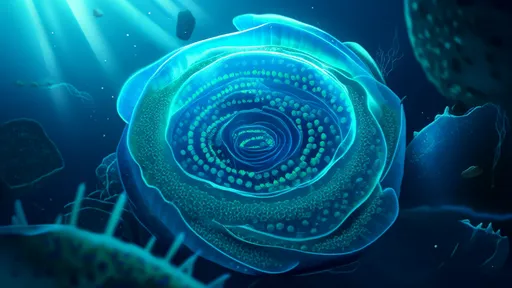

In the crushing darkness of the deep sea, where pressures exceed a thousand times that at the surface and temperatures hover near freezing, life not only persists but thrives. The organisms inhabiting these abyssal zones, particularly fish, have evolved nothing short of miraculous biological adaptations to withstand such extreme conditions. One of the most critical and fascinating of these adaptations lies in the very fabric of their cellular structure: the dynamic regulation of cell membrane fluidity. Unlike their shallow-water counterparts, deep-sea fish possess cell membranes that remain functional and fluid under immense hydrostatic pressure, a feat of biochemical engineering that continues to captivate scientists.

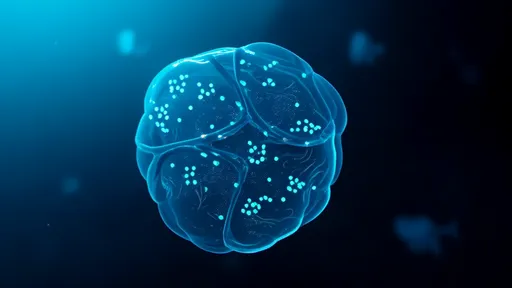

The cell membrane, or phospholipid bilayer, is the gatekeeper of the cell. Its integrity and functionality are paramount to survival. For most organisms, increased pressure leads to a decrease in membrane fluidity, a phenomenon known as pressure-induced rigidification. A rigid membrane compromises a host of vital cellular processes; it impedes the function of embedded proteins and ion channels, disrupts nutrient transport, and can ultimately lead to cell death. This is why shallow-water fish, brought to the depths, would perish almost instantly. Their membranes would solidify, ceasing all meaningful cellular activity.

Deep-sea fish have circumvented this existential threat through a sophisticated evolutionary strategy centered on lipid composition. The secret to their success is a high concentration of unsaturated fatty acids within their phospholipids. The structure of these unsaturated fats is key. They contain one or more double bonds in their hydrocarbon chains, which introduce kinks or bends. These kinks prevent the lipid molecules from packing together tightly. While this makes the membrane more fluid and less viscous at surface pressure, its true value is revealed under pressure. The kinks maintain molecular disorder, resisting the ordering and compaction that high pressure forces upon the membrane. Consequently, the membrane maintains a necessary degree of fluidity, a state biologists term homeoviscous adaptation.

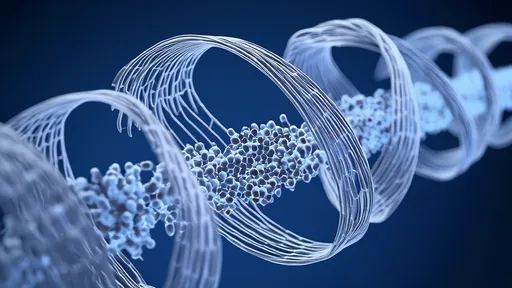

This adaptation is not a passive trait but a highly active and regulated process. Deep-sea fish meticulously control the saturation level of their membrane lipids through a suite of enzymes, most notably desaturases. These enzymes are responsible for inserting double bonds into growing fatty acid chains, increasing their unsaturation. The expression and activity of these enzymes are believed to be modulated by environmental cues, including pressure itself. It is a continuous biochemical fine-tuning, ensuring the membrane's physical state remains constant despite wild fluctuations in the external physical environment. This precise regulation is what allows a fish to conduct vertical migrations through hundreds of meters of water column, experiencing drastic pressure changes, without suffering cellular shock.

The cholesterol content within the membrane plays a equally crucial and nuanced role. Often misunderstood, cholesterol does not simply rigidify membranes. Its function is more that of a modulator or a buffer. In a highly fluid membrane, cholesterol acts to restrict the movement of phospholipid chains, adding a degree of stability. Conversely, in a rigid membrane, it separates the phospholipids, preventing them from crystallizing and thus increasing fluidity. For deep-sea fish, cholesterol serves as a vital rheostat, fine-tuning the fluidity provided by unsaturated phospholipids to an optimal level, ensuring that the membrane does not become too fluid and lose its structural integrity at depth.

The implications of this research extend far beyond marine biology. The principles of homeoviscous adaptation are providing a new lens through which to view human medicine and biotechnology. Understanding how proteins and enzymes function stably under high pressure is revolutionizing the field of enzymology. Researchers are studying deep-sea fish proteins to engineer industrial enzymes that can operate in non-standard, high-pressure conditions. Furthermore, the study of pressure-resistant membranes offers insights into conditions like ischemia, where cellular membranes in the human body can become damaged under stress. By deciphering how deep-sea organisms protect their cells, we may uncover novel strategies for preserving human tissues.

In essence, the humble deep-sea fish is a master chemist, performing an exquisite balancing act at a molecular level. Its cellular membrane is a testament to evolution's power to engineer solutions to the most extreme challenges. Through a deliberate and dynamic manipulation of lipid unsaturation and cholesterol content, these remarkable creatures have turned a potentially lethal environment into a home. Their survival strategy, written in the language of chemistry and physics, continues to offer profound lessons in resilience, adaptation, and the very essence of life itself.

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025