The rustle of plastic packaging has been the soundtrack of modern consumerism for decades, a ubiquitous noise signaling convenience, sterility, and progress. Yet, this sound has become a global dirge, a constant reminder of a pollution crisis that chokes our landfills and pollutes our oceans. For years, the search for a viable, scalable alternative has been the holy grail of materials science, a quest often met with promising lab results that falter under the harsh realities of industrial production and economic viability. That long-sought paradigm shift now appears to be emerging not from a high-tech chemistry lab, but from the quiet, damp undergrowth of the forest floor. The solution, it seems, has been growing in the dark all along.

The hero of this story is mycelium, the intricate, root-like network of fungal threads that constitutes the main body of a fungus. While we admire the mushroom—the fruiting body—it is the vast, hidden mycelial mat that is the true workhorse of the organism. This network is nature's ultimate recycler, a biological wizard that breaks down complex organic materials like wood and agricultural waste, binding them into a dense, resilient matrix. Scientists and entrepreneurs have learned to harness this natural process, guiding the growth of mycelium to form specific shapes and structures with remarkable material properties. The result is a fully organic, home-compostable material that can be engineered to possess the protective qualities of traditional plastic foams like polystyrene.

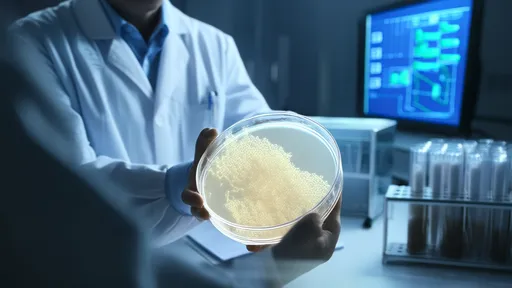

The journey from a petri dish to a pallet of packaging is a fascinating feat of bio-fabrication. It begins not with synthetic polymers derived from petroleum, but with agricultural waste. Substrates like hemp hurd, oat hulls, wood chips, or even cotton burrs—byproducts that would otherwise be burned or sent to landfill—are collected and sterilized. This nutrient-rich waste is then inoculated with mycelium spawn, selected for its fast growth and strong binding characteristics. The inoculated substrate is placed into custom-designed molds that mirror the exact shape of the product to be packaged, from a delicate wine bottle sleeve to a sturdy protective block for a large computer monitor.

Then, the magic happens in the dark. The molds are placed in a warm, dark, and humid environment—conditions mycelium thrives in. Over the course of a few days, the fungal network spreads relentlessly through the substrate, secreting powerful enzymes to break it down and then weaving a tight, white matrix that binds everything into a solid mass. This growth phase is self-assembling and requires minimal external energy; the organism does the manufacturing itself. Once the mycelium has fully colonized the substrate and reached the desired density, the process is halted through a drying and heat-treatment stage. This not only stops the growth but also renders the material inert, ensuring no spores are released and making it safe for consumer use. The final product is a lightweight, yet surprisingly strong, fibrous material that is ready to protect its contents.

For decades, the major hurdle for bio-based alternatives has been scaling production to meet the colossal demands of global supply chains. Pioneering companies like Ecovative Design in the United States and Biohm in the United Kingdom have spent years perfecting the science and, crucially, the engineering required for mass production. They have moved from small-batch artisan production to fully automated, large-scale cultivation facilities. These factories are not traditional manufacturing plants with injection molders and extruders; they are more akin to highly controlled agricultural environments or breweries, where temperature, humidity, and airflow are meticulously managed to optimize the growth of a living organism. This shift from crafting to farming at an industrial scale is what marks the true revolution. It proves that we can produce millions of units of protective packaging without drilling for a single drop of oil.

The environmental argument for mycelium packaging is overwhelmingly compelling. Its entire lifecycle stands in stark contrast to that of conventional plastics. It is grown from waste, not fossil fuels. Its production is carbon-neutral, or even carbon-negative, as the mycelium sequesters carbon from the agricultural feedstock and the process consumes very little energy compared to the high heat and pressure required for plastic manufacturing. Most importantly, its end-of-life is a return to the earth, not a persistent pollutant. After its useful life, mycelium packaging can be simply broken up and added to a home compost bin or garden soil, where it will fully decompose into nutrient-rich organic matter within a matter of weeks. It embodies the ultimate circular economy model: from waste, to useful product, and back to soil.

Of course, no revolution is without its challenges. While the cost of mycelium packaging has decreased dramatically with scale, it can still be more expensive than dirt-cheap, subsidized virgin plastics. There are also questions of consistency, water resistance, and shelf life that are being actively addressed through ongoing research and material blending. However, the momentum is undeniable. Major corporations, driven by consumer demand for sustainability and ambitious corporate environmental goals, are increasingly partnering with mycelium producers to integrate this packaging into their logistics. They are recognizing that the slightly higher upfront cost is offset by immense brand value and a significant reduction in their environmental footprint.

The implications of this shift extend far beyond simply replacing a bubble mailer. The ability to grow custom-shaped, protective materials on demand opens up new possibilities for sustainable logistics. Imagine a world where packaging is not shipped empty across oceans but is grown locally in facilities near major distribution hubs, using agricultural waste sourced from nearby farms. This would drastically reduce transportation emissions and bolster local economies, creating a truly distributed and resilient manufacturing model. The technology also holds promise for other industries, from construction materials and acoustic panels to vegan leather alternatives, pointing toward a future where more of the things we use are grown, not made.

The rise of mycelium packaging is more than just a new product line; it is a profound change in philosophy. It represents a move away from the twentieth-century model of extract, manufacture, and discard, and toward a twenty-first-century model of cultivate, use, and return. It shows us that some of our most intractable problems can be solved not by fighting nature, but by collaborating with it. By learning from the quiet intelligence of fungi, we are beginning to weave a new, more sustainable thread into the fabric of our civilization—one that leads not to a landfill, but back to the earth.

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025

By /Aug 27, 2025